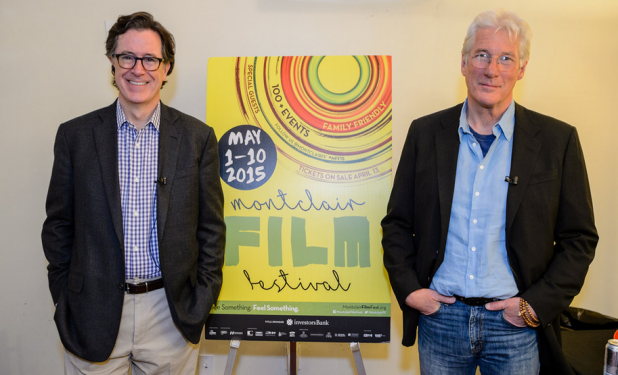

Colbert and Gere, Illuminating Convo

Cinema, the philosophy of life, and a truth universally acknowledged that every mother loves Richard Gere: in an extremely lively, funny, and illuminating chat on Saturday at the Wellmont Theater, Stephen Colbert and Richard Gere discussed and debated everything from Gere’s newest film (Time Out of Mind, about homelessness, which premiered directly after this In Conversation series) to the Buddhist nature of reality.

Following MFF director Tom Hall’s opening quip about being remiss if he didn’t mention his mom’s affection for Gere, Colbert instantly grabbed the opportunity to say he himself would be remiss if he didn’t mention his GRANDMOTHER’s love of Gere. After Gere good-naturedly related his experience of having THREE generations of women approach him while filming in Sarajevo, the two men moved on to the matter at hand: Gere’s newest release. Colbert praised the movie, calling it a “a rare film, that makes something sad but beautiful at the same time.” Gere referred to his character as “a refugee without a place” but asserted that despite the fact that it’s called “that homeless movie . . . by the end you go beyond that narrow definition.” Colbert noted that “many were kind to kind to him [Gere’s character], some cruel,” to which Gere responded that his character had a bureaucratic system he had to navigate but there are no bad guys.”

Although Gere did much of the filming out in the open, because he remained completely in disguise as a homeless person, most passers-by generally didn’t recognize or pay attention to him. (A French tourist, seeing Gere dig into garbage for scraps, did offer him food, while another man simply said “Hi, Richard”). Discussing the film’s technique and style, Gere spoke of how the director shot with a telephoto lens, often shooting through obstacles like glass and leaves, which helped keep the audience at a distance; most of the sound was ambient and the film has no musical soundtrack. Gere described his character as “still, while New York is moving . . . He sticks out because he’s quiet and still in a world of movement.”

Colbert then noted that we never know exactly how the protagonist ended up in that situation; we really aren’t given his backstory. Gere added that even the clues we are given about the character’s past can’t really be trusted, because he may be lying. He mentioned, as well, that he worked very differently on this movie, choosing a more open and intuitive process than usual. That cued Colbert to go back to Gere’s early days as a struggling young actor. Gere got his first job in the renowned Provincetown Playhouse (he actually accompanied a friend to the audition as a lark) and only earned $28.00 a week. Colbert wondered whether Gere had ever gotten close to being destitute early in his career; he admitted that he hadn’t really, although he prepared himself to experience hard times.

Colbert then jokingly began to discuss something the two men had in common: their appearance in People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive” issue! (Gere received the ultimate honor when he was about 50 years old; Colbert appeared in the magazine but didn’t earn the top spot). After teasing each other about the longevity of their sexiness (“It’s insane how long my sexiness has lasted,” Colbert joshed), the conversation veered back to the subject at hand: the invisibility of the homeless, as opposed to the extreme visibility of those possessing beauty and celebrity. What, Colbert wondered, does our country’s worship of fame say about our willingness to look at the dispossessed? Sexy people, he pointed out, are noticed regardless of how little they do, while no matter how much someone homeless tries to get ahead, no one looks. Gere described being homeless not as being invisible, but as being in a black hole: in his opinion, people were afraid to get close to someone homeless, afraid to be sucked into that bad luck. While Gere was in character, he could see pedestrians two blocks away making the decision to avoid him.

Noting that he was the same guy either way—as himself or as the “homeless” person people saw while he was playing that role—Gere spoke of the unreliability of surface, of the fact that our eyes are lying to us. This opened up what became a recurring debate between the Buddhist Gere and the Catholic Colbert throughout the talk: what is reality, and do we, as humans, have the ability to discern an objective reality. Colbert believed that we could, while Gere felt otherwise. In his view, humans tend to catalog things and then can only view the world through those already-fixed perceptions. “We’re only seeing our own mind. So all the prejudices, experiences, things in the catalog, we make the initial fresh event fit the category descriptions in our head,” Gere said. “We don’t have an experience of the world. We have an experience of our experiences. This is all a virtual world. The whole thing is virtual, based on our own brain.” “Is this the matrix?” Colbert queried. While Gere did admit that something might exist objectively, it doesn’t exist the way we think it does, and is unknowable. At one point, he insisted, “All the mind can do is see itself.” The usually unflappable Colbert responded: “You are blowing my mind, Richard Gere.”

Moving from the screen to real life, the two discussed which organizations did the best work with the homeless (Gere opted for the Homeless Coalition, whose offices were used in the film), and the recent tragic earthquake in Nepal, a country with which Gere had been involved and where he “has lots of friends and teachers”. Once again venturing into religious territory, Colbert asked Gere how he became a Buddhist and about his spiritual upbringing. Raised as a Methodist, Gere spoke of learning Christian compassion and grace from his father, as well as a caring for the larger community. But for greater wisdom, for looking into the mind, he found sustenance in Buddhism, which is a “science [and has’ no creator, no end. Our minds are so vast there’s no need for a creator.” He agreed with Colbert that Time Out of Mind has a Buddhist aspect. Making one last attempt to debate at the question of the real versus perception, Colbert asked Gere if he were to stab him with the Dasani bottle he was drinking from, would that be real? Gere stuck to his guns; even with the gore and the blood, no it would not be an objective reality as the two of them would perceive the action differently! The real has to be non-perceptual.

The floor then opened up to questions, with many in the audience playfully adding a little comment about their mothers to the query. (Gere gave a shout out to one 85-year-old Rita with an “I love you”). One person asked how Gere had taught his son, Homer, to give back to the community, The schools Homer went to had a part in that, Gere responded, but he didn’t push this on his son. “But if you’re loving and caring, your kids will become loving and caring” by example. A second questioner mentioned how much he loved Chicago and asked whether Gere planned to do any more musicals. “I’d love to!” he exclaimed, and mentioned that because he played a number of instruments, his first jobs were for Broadway musicals (he also played in rock bands). And Chicago was “so much fun” that he wondered why he’d ever stayed away. He praised the film’s director, Rob Marshall, for creating an atmosphere of “pure joy” where everyone got along beautifully.

Returning to the subject of the night, homelessness, the next questioner—who studied public health—asked whether, when he’d spoken to the homeless, they ever mentioned their health issues. “I can’t say they really talked about these problems,” Gere answered, “but they were so obvious”. Keeping people in their homes was crucial, he added, because without that structure they enter into a kind of “dreamtime” that takes over and ends up affecting their mental well-being. Gere felt that most of us, put in the same situation, would experience the same deterioration. “And even if they go crazy, no one pays attention,” he added, noting that since the Reagan era, money that went to mental health has been taken away, making all our lives more insecure.

A Pretty Woman fan—male!—spoke up next, acknowledging that he’d seen it more than 200 times as a child . . . thanks, of course, to his mom, who loved the movie and watched it every single day. On a more serious note, he then asked Gere how he incorporated gratitude into his life. “It’s every day,” Gere answered. “I’m incredibly fortunate,” he said, pointing to his career, his son, his good health. “Being a human is the top we can get. Why? We have intelligence. Way more than we realize.” That intelligence makes us suffer, he admitted, but “the sky’s the limit for us, there’s nothing that we can’t accomplish. The gratitude’s for that.”

After offering some praise for Stephen Colbert, the next speaker inquired, in a two-part question, about Gere’s Buddhist practice, and also how we can get more people involved in fighting homelessness. Gere began by meditating, although he warned that nothing comes from that quickly; it’s a long process, with small, incremental gains and many plateaus. But “It’s a commitment that goes beyond life”. At the start, he also began to recognize the pain and suffering in the world and cried a lot—but he has also grown to realize that means we are all in this together.

Regarding the homeless situation, Gere noted that many of his homeless friends were in the movie, and praised New York as the only state where you must legally be given a bed if you need it—something he feels every community should do. To help, Gere felt it was simply important to have a roll of dollar bills and give them to the homeless people you encounter, and also to make eye contact with them, as the communication may be even more meaningful than the money.

Gere ended the afternoon with a Buddhist-inspired parable about how making a change in your life can begin with the smallest gestures. A very wealthy man who wanted to help by giving money to those in need simply found it impossible to do so, no matter how hard he tried. The suggestion he had received: since his money was always in the right pocket and he would give with the right hand, he had to start by putting the cash in his left pocket and using his left hand. And so the process of transformation began . . .

And, to Stephen Colbert, thanks for his work, and wish for his continued happiness, Gere rose to tumultuous applause.

Written by MFF Blogger Karen Backstein