Nelson George: His Body of Work

by Karen Backstein

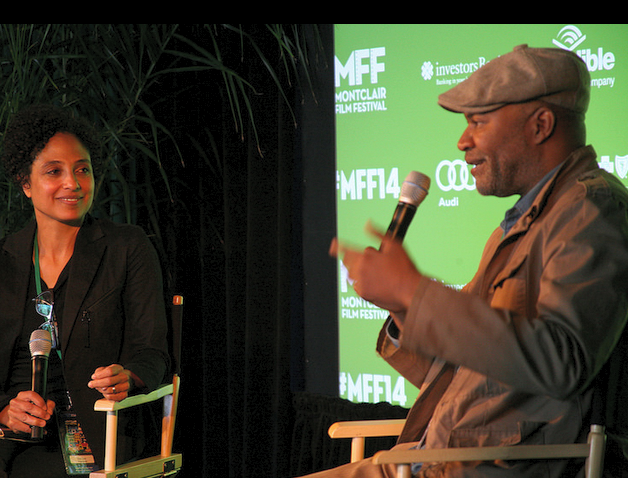

From producing the Chris Rock Show to directing such films as Finding the Funk, All Hail the Beat, and Brooklyn Boheme, the multi-talented, Brooklyn-born Nelson George has explored various facets of African-American culture. On Saturday, he came to the Audible Lounge to kick off a series of three panels presented in conjunction with Blackhouse films, an organization dedicated to expanding opportunities for black filmmakers that has earned great respect in the film festival circuit. This is the second year Blackhouse has joined the Montclair Film Festival, and Festival Director Thom Powers stressed how important this collaboration was to him and how much he wants to see it grow.

George, who began his career as a music critic for Billboard magazine and has a new book out on the popular 70s TV show Soul Train, focused on the art of writing and directing and treated the audience to footage of his newest work in progress, a film on the African-American ballerina Misty Copeland. Shola Lynch, Curator of film at the prestigious Schomburg Center, conducted the question-and-answer session, and began by giving the audience a long list of George’s achievements, as producer, director, and writer—some of which he himself joked didn’t even remember—although, for most, he provided back stories about contributors and collaborators. In particular he spoke about Brooklyn Boheme, an exploration of that borough’s thriving African-American artistic scene in the 90s. The people profiled in that documentary include some of today’s most influential artistic creators, among them Spike Lee, Russell Simmons, and Chris Rock. George reminisced about his longtime friends: he described Spike Lee’s apartment filled to the brim with the type of filmmaking equipment that “now would be done on a Mac.” More importantly, Lee showed George early footage of She’s Gotta Have it!, Lee’s first feature, which George invested in with a cash gift of $300—the first money he earned from his book Hip-Hop America and a lot for him back then. Lynch approvingly noted that it showed George’s generosity and proved that being successful doesn’t necessarily mean being cutthroat.

In fact, as George went on to emphasize time and time again throughout his talk, the most important thing to him, then and now, is community. Even though when they first met, Russell Simmons was a DJ at a roller disco, Lee still worked as a messenger, and Chris Rock was doing gigs in Saskatchewan, the group all supported each other and maintained their friendships. With this in mind, George had a word of advice for all young people entering the business: while mentors are important, even more so are the people you meet in your own age group, on your same path. Peers, as he pointed out, can pass along information, news, and opportunities. Build relationships, he stressed, because a strong bond is formed when you come up together.

Lynch asked George how he’d moved from music writing to film. He pointed to the energy in the era just after Spike had his first hits, when there was a sense of optimism about black cinema. Different projects popped up during this time, and people started companies, creating opportunity within the community. George also noted that he enjoyed the camaraderie of filmmaking, as opposed to going home and writing alone, but also felt that the move to documentaries from journalism felt very organic to him. One particularly meaningful project at this time came from HBO: a film called Life Support about people living with AIDS. It was a subject dear to him because his sister had the virus and only managed to survive because new drugs like AZT came out just in time; she went on to work in AIDS outreach, helping other HIV+ women . He used her in the film, as well as other women in her community, as a form of Greek chorus.

At that point, he introduced his new film on Misty Copeland, the first-ever black soloist for American Ballet Theater, author of a new autobiography, activist, and role model. George knew her only from her dancing with Prince, and when he learned she did ballet, he asked for a ticket to one of her shows—and went to see her do Firebird. At the esteemed Metropolitan Opera House, he was blown away to see her image on the company‘s big poster for their spring season. But it turned out that Copeland had been dancing with five fractures in her shin; she was lucky that the bone didn’t snap. George captured every step in Copeland’s excruciating journey back from surgery and rehab, a lenthy process that sidelined her for a year and a half—an eternity in a ballerina’s career. We saw her first tentative non-ABT performance, dancing “The Dying Swan” at BAM’s Fishman Center; a doctor’s visit seven months post-surgery where she discussed the traumatic nature of her injury; and her rough return to American Ballet Theatre. After a poorly received performance, Copeland, nearly in tears, determinedly rehearsed and rehearsed the steps that had eluded her, resulting in a better show the second night. Perhaps the most special sequence was the last: Misty on stage alone, bathed in the spotlight, beautifully dancing a solo from the ballet La Bayadère—all gorgeously filmed and edited.

Afterwards, George praised Misty for her strength in dealing with the tradition-bound ballet world. “There’s never been anyone like her,” he stated firmly, noting how she stood out not only for her blackness but for her more curvy figure among the rail-thin ballerinas. He also remarked that he considered this a very intimate film, for he himself is on screen, questioning her and encouraging her.

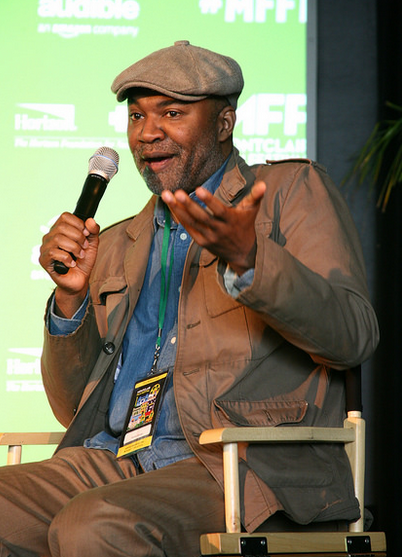

George then took questions and answers from the audience. Asked about how he sold his works and whether he had an agent/manager, he said most of his work was self-created, and that he “just starts shooting” when he has an idea. Lynch added that George was incredibly entrepreneurial. “I don’t go asking for permission,” he said, and warned any prospective filmmakers that with today’s cameras, editing, and sound equipment there was no reason not to go ahead and shoot in this day and age. ”You MUST shoot to pitch,” or don’t bother.” and finished by saying how much he loved the phrase “body of work.” For George, it’s important to be more than a one-hit wonder, and he most strongly admires people who work in many different media and simply have an interesting life. “Test your limits,” he advised, “even if you fail.”

Click here for more pics of this event!