In My Father’s House: Ties that Bind

An abandoned son, a homeless father, the ravages of addiction, a suffering community, patterns of abuse and neglect, the healing power of a solid marriage, and the extent to which forgiveness and redemption can be won are just a handful of the themes explored in Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg’s incisive documentary In My Father’s House, which played for a rapt audience at Clairidge Cinemas on Saturday.

Winner of the Documentary Audience Award and Overall Audience Award at the Nashville Film Festival, In My Father’s House is the story of Grammy- and Academy Award-winning hip hop artist Che “Rhymefest” Smith, who, despite multi-million dollar record contracts and celebrity connections, has long been plagued by the emptiness of his father’s absence. Looking to buy a house in Chicago, Smith serendipitously discovers his father’s former home on the market and—perhaps to feel closer to his dad—makes an offer. Shortly thereafter, the specters of his past haunt him. “Where were you?” he writes in an open letter. “Did your father abandon you?”

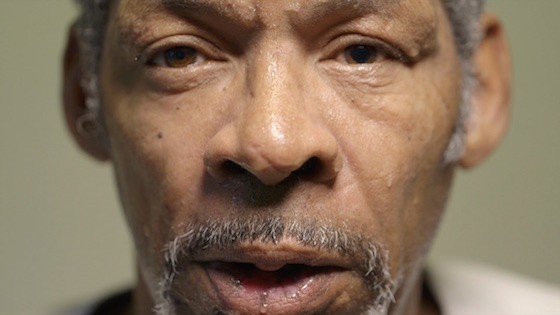

With encouragement from his wife Donnie (herself the product of a broken home), Smith seeks out his father, Brian Tillman, a homeless alcoholic he’s neither seen nor heard from since childhood. Before meeting at a local library, Smith expresses anxiety about whether he has made the right decision; he isn’t even sure what to call Tillman. After some initial awkwardness, however, Smith falls into an instant camaraderie with Tillman. Smith is an endless reservoir of compassion: “I’m a piece of him,” he says. “Maybe I can help turn things around for him.”

What follows is an equally hopeful and crushing portrait of broken sons chasing after broken fathers. Can Smith help Tillman conquer his demons, and mold him into the father that Smith has always wanted? Or are Smith’s dreams of his father’s redemption futile? What then? These are questions any child of an alcoholic has asked himself, and there the film’s broad reaches are revealed: Forgiveness and acceptance are a complex business, and the trajectories of pain set in motion by abuse and neglect reach far and last long. “I was that kid gangbanging,” recalls Smith. “I felt like a failure because I didn’t have a father.” In an electrifying scene, Smith visits a community center and listens to a young man deliver a rap about violence. “Your daddy died when you were young and your brother just died, and you’re rapping about robbing and killing someone?” Smith asks. “That’s your most profound rap and you’ve got it right inside you.” The teen’s tough exterior crumbles, his shoulders curl inward, and he weeps as though his soul were shattered.

Following the screening, director Ricki Stern and producer Jameka Autry took questions from the audience. The crowd was so deeply moved by the film that many shared personal stories of their own journeys with absent parents and addiction. Stern detailed how the project really initiated with Smith, who began filming his search for Tillman on his cell phone; in fact, the reunion scene in the library was filmed by Smith. “We watched the footage and I felt like this was a universal story,” Stern said. “Finding one’s parent, finding who you are, and knowing your legacy—it’s something that a lot of people can relate to.”

When asked if she felt her subjects were ever withholding, due to the intimate and difficult nature of their story, Stern elaborated on the process of making a documentary and developing deeper connections with her subjects. “We film people sometimes for years, so you develop a kind of friendship with them,” she said. “We filmed [In My Father’s House] over 18 months. It was really about maintaining that intimacy, understanding what was going on for them.” While her subjects remained emotionally available throughout filming, the shooting process and the presence of the cameras did wear on them after a while. “You get to this point where you’re like, ‘All right, I’m going to be there at six in the morning!’ and they’re like, ‘Really? Again?’” Stern offered.

Stern also expounded on the role of the documentary filmmaker and to what extent she should be objective. “As I’m going through it with Che and Brian, I’m really experiencing it through their eyes, and I think I very much have that distant perspective. I almost found myself counseling them. I know documentary filmmakers aren’t supposed to do that, but I’m over that,” she said, drawing laughs from the audience. “At a certain point, you don’t want to abandon them, and you don’t want to see them abandon each other.”

Autry added, “I think, behind the scenes, we learned a lot about race, because we had a lot of internal conversations about race.” This prompted several audience members to comment on their personal connections to substance abuse and single-parenthood in the African American community, and what positive takeaways they culled from the film. Other audience members offered support and love to the ones who voiced their struggles and journeys that mirrored Che and Brian’s.

Stern and Autry also discussed their plans for the film’s future. They are currently proposing educational guides edited for schools, prisons, and parent groups as well as shopping it around to sales agents. The film heads next to the Bentonville Film Festival (Bentonville, AR) before making its way overseas to the Documentary Edge Festival (Auckland, NZ).

Written by MFF Blogger Michael Traynor