Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck

For the young protagonist of Nick Hornby’s hugely popular book About a Boy, Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 marks the end of the world, the day the music died—and he is not alone, especially for fans of that generation (the late 80s/early 90s), who helped Nirvana zoom to the top of the charts. One of rock’s most potent icons, Cobain’s too-early death at only 27 years old has spawned a rash of conspiracy theories, and even intimations of murder. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, produced by Cobain’s daughter Frances Bean and made with the cooperation of his wife, Courtney Love, bypasses those rumors in favor of a deeply nuanced look into the man, his life, his career, and his personality.

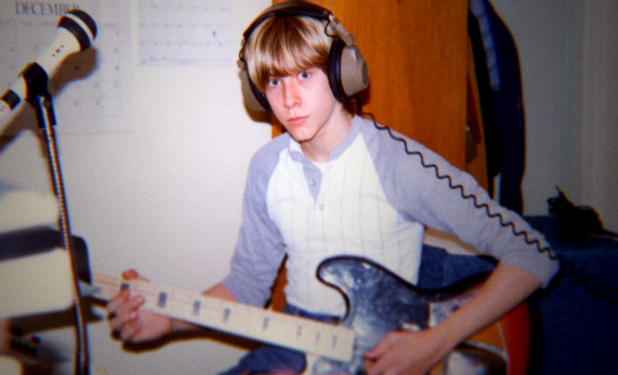

“Montage” is in fact the perfect word to describe this already much-praised documentary, which plunges into Cobain’s world through a rich variety of materials and techniques—much of it previously unseen materials that only director Brett Morgen was given access to. The film weaves together archival footage, including early home movies in which the sweet-faced, golden-haired boy gazes and throws kisses at the camera, as well as later video taken in his and Love’s apartment; lavishly animated sequences, often with anguished voiceover from Cobain’s personal writings; performance clips and appearances on MTV and elsewhere; and a limited number of talking-head interviews with Cobain’s mother, father and stepmother, sister, ex-girlfriend, Love, and bandmate Kurt Novelisec.

Nirvana’s music blasts over some of the images from the 60s, pointing toward the troubled future, rather than presenting his childhood nostalgically, as a time of innocence. For Bean, who was a baby when Cobain killed himself and appears only as an infant in the family movies, helping to create Montage of Heck must have been an act of reconstructing her father, or trying to meet the man she never really had the chance to know. Indeed, some of the most poignant images show Cobain gently and lovingly cuddling his small daughter—the daughter who, he claimed, had led him to straighten himself out.

This is not a film that offers a simple explanation of why Cobain took his life. Again, like a montage, it aims not to tell the audience what to think but allows them to draw their own conclusions from the treasure trove of material; we have to put the various pieces together in a way that makes sense to us.

The portrait painted by the documentary reveals a man who, even from the youngest age, seemed to have intense, sometimes destructive, energy; extraordinary sensitivity to criticism; and a much greater-then-usual inability to deal with being humiliated. In one of the first interviews we see, Cobain’s sister states that “I am so glad I haven’t got that genius gene,” and the question of nature vs. nurture in his misery is implicit. Difficult to handle as a child, he was shunted from place to place after his parents’ divorce, repeatedly kicked out of various family members’ homes until being unceremoniously dumped back at his mother’s door; his stepmother, Jenny, felt he “wanted the perfect family, but no one would keep him.” Prescribed Ritalin, he had a terrible reaction to the drug and as his mother says, “went off the rails.” His journals from those days, and through the teen years, reveal a propensity to violence and self-harm, as well as an already strong desire to end his suffering through suicide.

But the footage also shows a young Cobain with his guitar, revealing how early an interest in music manifested itself. (Although, given his post-punk aesthetic, his “Rule #1” was “learn not to play your instrument.”) And his and Nirvana’s success came relatively quickly, unnerving his mother, who worried about his ability to handle fame. When she heard the demo of Nirvana’s first record, she instantly realized that nothing would ever be the same for him again. The band’s first interviews confirm her fears, as they, and Cobain most particularly, renounce the idea of being stars. Later, they apparently grew more comfortable with the idea of being idols. The sequences taken during his marriage with Love captures Cobain’s downward spiral both through both the camerawork and content: generally shot by Love herself, the footage trembles, jiggles, and wobbles as she films, visually conveying a sense of chaos and instability. There’s no serenity in what the images reveal, either, and certainly no feeling of rock-star wealth in the surroundings. Their life together—marked as it was by heroin addiction (Frances was born addicted to methadone) by one or both at any given time—clearly was as shaky as the shooting, although the documentary itself doesn’t pass judgement on either Cobain or Love.

In the end, we can never know why Cobain chose to kill himself —and this being a film made in cooperation with his family, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck treads carefully on the subject. While it doesn’t offer answers, it gives us a fascinating look at a troubled genius whose music caught the spirit of a generation.

Written by MFF Blogger Karen Backstein