Belafonte at NJPAC!

by Karen Backstein

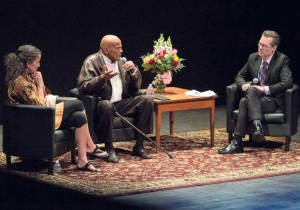

A celebration of Harry Belafonte—his life, his work, and his politics—took place at NJPAC in Newark on Sunday, April 28th. A kind of “pre-game” event before the Montclair Film Festival officially started the following evening, it featured a screening of the 2011 documentary Sing My Song, followed by a post-movie discussion with Belafonte himself and his daughter Gina (the film’s producer), led by Festival Artistic Director Thom Powers.

For those who know Belafonte only as performer, the documentary showcases a different side of the man. While it includes numerous clips of him singing his most popular songs—the slyly witty “Man Smart (Woman Smarter),” “Jamaica Farewell,” “Scarlet Ribbons,” and of course “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)”—the film doesn’t examine his career in a vacuum. Instead, it smoothly blends biography and art with a rich portrait of Belafonte the social crusader, determined to break racial barriers and fight injustice wherever he saw it.

Belafonte lived through extraordinarily tumultuous times and the documentary covers Belafonte’s experiences with segregation; his participation in the civil rights movement and friendship with Martin Luther King, Jr.; his protest against the Vietnam War, and later, US intervention in Iraq; his battle against South African apartheid and comradeship with Nelson Mandela; right up until the present, when he continues to be deeply involved with issues of violence and the increasing incarceration of poor young people. He was there marching on Selma and in Washington, and risked his life many times over during the most heated battles of the civil rights era. He convinced both President Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy to listen to him and shift their point of view on equality, criticized President Clinton’s stand on Haiti, and never ceased to call it as he saw it—even when speaking about America’s first black president.

As Belafonte noted during the post-film discussion, “I was an activist who became a singer, not a singer who became an activist.”

Given the world he lived in, even what might have seemed like a simple performance often became an act of courage. Twice, the fact that he merely touched a white woman on stage set off a storm, and a racially mixed cast for his TV show proved unacceptable to the network. He watched, frustrated, as film scripts that had seemed progressive at the start were altered at the last minute because the studios got cold feet, especially when the stories hinted at interracial romance; his answer was to form his own independent production company years before anyone coined the term “indie filmmaking.”

On a personal level, when he toured with other musicians and dancers, he often could not stay at the same hotel or dine with them; his real-life marriage to a white woman brought out ugly poison-pen letters from people wishing them ill. At the same time, his popularity proved groundbreaking and record-setting, winning him Grammys, gold records, and a multiracial fan base practically unheard of at the time.

Rich in archival photos, movie clips, and newsreel footage of Belafonte’s performances as well as of influential artists, famous friends, and history-changing activists, Sing My Song captures victories both big and small, successes and fallbacks, and the need to remain ever vigilant in the fight for freedom. Not surprisingly, the documentary encourages viewers to get involved as well—not to be a passive audience, but to join in. And literally join in the audience did, as “Day-O” played over the credits, everyone sang along with the chorus. Daylight come . . . but no one wanted to go home as the discussion and Q&A began.

Belafonte’s outspokenness—his firm moral center and conviction—was more than evident in the lively discussion that followed the screening. Thom Powers began by asking Belafonte what prompted his book (an autobiography called My Song) and the film. Belafonte responded that the major impetus came from the death of his good friend Marlon Brando; he was saddened that Brando “took his history with him” when he died and felt it was important to show how activists used the power of celebrity to effect change. (Plus, his daughter had been nagging him to write the book.)

He went on to answer Powers’s questions about the wonderful researchers who “looked under rocks” to find the wealth of archival material that enriched the film—and then spoke about HARBEL, the independent film company he’d formed in the 1950s. Belafonte had hoped to make movies in which he wasn’t playing a subservient character making jokes to hide the pain of racism.

A central question for him was how he, and other emerging black stars like Sidney Poitier, could change public perception of black life and, especially of black men, as culturally inferior. He no longer wanted studios filtering his product, and he was grateful to the people who “helped [him] get past the hurdles of the studio system,” like director Robert Wise (known for West Side Story) and actress Shelley Winters. Still, Belafonte admitted that the financial realities of such a venture at the time were extraordinarily difficult, and that “he is still paying to this day.” He spoke scathingly of the banks and large businesses that he had to deal with during that time and that still, in large part, control cultural outlets.

Moving to the question of his involvement with the civil rights movement, Belafonte credited people like Eleanor Roosevelt and Paul Robeson for mentoring him. Acknowledging the anger he felt at how he was treated during those days, Belafonte detailed his journey from “by any means necessary”—the credo of Malcolm X—to the mentality of nonviolence preached by King. With King, he had to the chance to deal with strategy and find ways to articulate the goals of the movement through the creation of culture. Belafonte quoted Paul Robeson’s words that “art is for the gatekeepers of truth,” and asserted that art is the radical voice of civilization.

Gina Belafonte addressed Thom Powers’s question about how to reclaim the urgency that seemed to exist more strongly in the 1950s and 60s than now, remarking that the Civil Rights movement had shown people that change was possible—and that many different groups, including women and gay rights activists, had used its strategies to foster change in their own lives. She urged the audience to find something “they can align themselves with” and get involved—a point echoed by her father numerous times during the discussion.

Even in this age of Obama, Belafonte asserted that racism is “alive and very active,” and dismissed the idea that we live in a post-racialist moment. “Insanity is going on right now,” he noted, pinpointing the actions of the TV party and pointing out, as well, that the US has the largest prison population in the world—something he and many social critics view as a method of control. One difference for him, however, is that everything in the 50s was visible while racism today goes “underground.” Above all, he stressed the need to be vigilant because “democracy forces us to be alert” if we wish to keep our rights alive.

In response to Powers’s direct question about Obama, Belafonte stated he had “long since come to a place where Barack Obama is first and foremost a human being.” He praised what he saw as the choice America made by putting him into office during the first term, that it created an image of what he wanted America to be and hoped would prevail. Yet his disappointment at what had not been accomplished came through clearly. Interestingly, for Belafonte, the last political high, the last politician he considered to have a “philosophical command of where we should be as a nation morally,” was Robert Kennedy—a man who, the film makes clear, he initially didn’t feel very sure of. ‘

As the conversation continued, Belafonte passionately and articulately covered a wide range of subjects that concern him, from the reactionary media to climate change to capitalism’s view of other nations as “cheap markets to exploit.” When the audience got their turn to question Belafonte, many of the speakers proved equally passionate as they queried him on where we could find today’s leaders; on whether nonviolence as a practice could work anywhere, including within the most repressive governments (Belafonte firmly felt that it could); and what we as a nation could do about the troubling prison situation in our country where so many young blacks were incarcerated. The woman who asked that last question—a professor who worked with inmates—scored an invitation to come backstage to talk about what she was doing and what further possibilities for organization and change might exist.

Sadly, with so many people eager to talk, the time ran out before everyone could get an opportunity. As Harry Belafonte left the stage, the audience stood and applauded, honoring one of America’s great men of music . . . and conscience.

Here is a clip from Harry Belafonte’s interview with Thom Powers at NJPAC on ReelblackTV: