Every Day is a Holiday

by Tanya Manning-Yarde

After his mother’s passing, a centenarian of wise years and generous heart, my cousin began renovating his Brooklyn childhood home. Pulling up well-lived carpets, he discovers the floor underneath protectively covered by newspapers from 1947, the year his parents purchased the brownstone. Resourcefully, he did not quickly discard the papers, fire hazard they may have been. Enthused by this archaeological discovery, he combed the articles, even finding a front page story about famed baseball player Babe Ruth. He plans to frame it and others in homage to the history upon which his family unknowingly walked their own.

Similarly, Theresa Loong discovers the pièce de résistance of her father’s life as he shares with her his wartime diary while ill. A literary heirloom, she could rightfully have chosen to keep it to herself, remaining the sole beneficiary of his innermost thoughts and wisdom. Unselfishly, she deems her inheritance too important not to divulge. She unfolds both diary and daddy in the documentary Every Day is a Holiday.

A perspicacious filmmaker, Theresa unearths the bones of her father, breaking open the marrow of his lifelong resolve to endure challenge after challenge. The documentary begins with his intimations of being a prisoner of war in Japan during World War II from 1942 to 1945. At just 19 years old, he candidly details the exploits suffered within Mitsushima and Hitachi prison camps. Shoveling sand, breaking rocks, bagging cement, toiling in dangerous hot copper mines wearing tattered clothing, hunger festering until fights break out over grains of rice, are just a few of the atrocities recorded within his words. Dr. Paul Loong recounts that the captured soldiers were transformed by the mercilessness and brutality into “walking skeletons full of dirt and rice.” Together, father’s pen and daughter’s lens harmonize, bringing into sharp focus the horrific inhumane physical conditions and mental anguish he and his comrades endured as POWs for three years.

The diary serves as a portal into the deepest realm of her father, a space he did not disclose to fellow prisoners, and not until late in age when he believed his daughter could understand. Justifiably, Dr. Loong’s writings and life thereafter could focus predominantly on unbosoming a chronicle of despair. However, his entries do not break bitter. His written expositions, and the life they have taken on ever since, contradict captivity. The imprisonment does little to chip away at his steadfastness or eclipse his tenacity. On August 15, 1945, he and over 45,000 imprisoned soldiers were finally liberated. He records his renewed conviction in a better life by writing “Every day will be a holiday.”

The epiphany of celebrating life and cherishing liberty has informed his daily living ever since.

Every Day is a Holiday situates the snapshot of Dr. Loong’s period of imprisonment within the larger photo album of his life. Like a favorite uncle sharing his life story during a family reunion, we are invited and drawn into Dr. Loong looking back on his trials, tribulations, and triumphs. Deftly, Theresa dredges his diary, capturing his pithy observations and beautiful prose, juxtaposing highlighted excerpts with photos and videos of his life since the camps. Her digging uncovers that his attention and motivation are emphatically centered on future possibilities. It is from this center that an even greater story unfolds line by line, reflection by reflection.

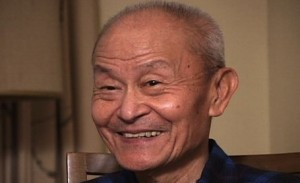

Theresa weaves a compelling narrative of the testing of her father and how each test actually served as a compass. We are beguiled by one-on-one interviews of his accounts of becoming self-sufficient in an unknown country, securing U.S. citizenship amidst many deliberate roadblocks, pursuing an education and career in medicine, and preparing to financially sustain a family. Family photos, as well as on-location and archival footage, illuminate and illustrate her father’s evolution. Candid interviews capture her father’s humanity; his fertile mind, fragility, and funniness. Like sitting at the knees of an elder, Paul Loong dispenses humor, compassion and honed clarity. We learn he is a complex man who despite tests of faith, patience and strength, does not remain trapped in the tests. One incident does not a life make, and Theresa craftily shows this by positioning her father’s memoir within a larger conversation about humanity and resilience.

Following the viewing, the audience had the opportunity to meet and talk with not only filmmaker Theresa Loong, but also her mother and father, as well as executive producer Bill Einreinhofer. The audience posed questions about the making of the film and also to the family. First, Theresa was asked about what brought her to do this film. She shared that the idea for the film germinated while interning at Channel 13 and grew from a family visit back to Mitsushima. She thought about how personal stories can easily go unexamined and unexplored, and thought about how the intersection of storytelling and film could best suit the telling of her father’s particular story. An audience member then asked Dr. Loong whether he remains in contact with fellow POWs. He shared that he maintains correspondence with a few that are in Canada as well as the widows of POWs who are deceased. However, because many have passed, correspondence is now within a community of the children and grandchildren of the deceased. Another viewer asked how Dr. Loong was able to travel from Chicago to New York during the period when he was still trying to secure citizenship, which Dr. Loong then explained through telling of his non-unionized service on an oil boat. Next, Dr. Loong was asked, “During the most difficult times in life, what sustains you?” He humbly replied, “My belief in God’s goodness.”

Next, Theresa was asked how she managed to get the film funded and completed. She explained that she worked on the film for nearly a decade as a side project and then found support and financial backing from Kentucky Educational TV, ITVS, The Film Shop and Kickstarter. Finally, both Dr. Loong and Theresa shared about an unanticipated experience in doing the film together. He shared that it was difficult to do the movie because it brought up very sad memories, something which Theresa disclosed that she did not realize the painful impact of recalling what happened as well.