News

The Ties that Bond in TRE MAISON DASAN

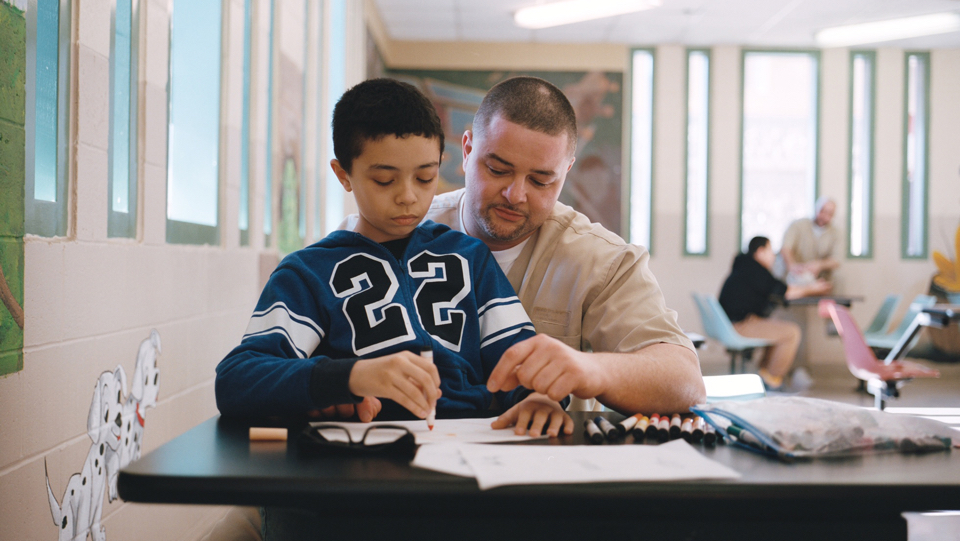

Denali Tiller’s TRE MAISON DASAN is an urgent story that explores parental incarceration through the eyes of three boys. Following their interweaving trajectories through a childhood marked by the criminal justice system, and told directly through their perspectives, the film grapples with the legacy of incarceration on growing up and the struggle to define what it means to become a man in America. Hilarious, heartbreaking, uplifting, and ending with tremendous hope, Tre, Maison and Dasan’s lives are stories far too often experienced, but rarely told, filled with struggle, loss, empathy, resilience, and, ultimately, unconditional love.

Montclair Film Festival was pleased to talk to with Director Denali Tiller about her intimate and gripping documentary.

How do you describe TRE MAISON DASAN in your own words?

TRE MAISON DASAN is named for the three boys at its center — each of them growing up with a parent in prison. Through intimate relationships with the filmmaker, documented in true vérité, the film reveals the experience of parental incarceration directly through the child’s perspective. The kids’ everyday, often funny and heartwarming experiences are wedged between powerful, deep moments between them and their incarcerated parents in the visiting room and at home. Their stories expose the incredible importance of incarcerated parent-child relationships, normalizes their circumstances and dismantles the stigmas that surround them both.

What made you want to tell this particular story?

In 2014, I met Joyce Dixson-Haskett, who had been incarcerated for 17 years in Michigan. Her sons were 6 and 8 years old when she went to prison, and 23 and 25 when she came home. When she got out of prison, she got her master’s in social work and created a psychological model that outlines the cycle of grief and trauma that children go through when presented with the unique challenges and stigma of having a parent arrested and locked away. Her model was developed into a parenting program at the John J. Moran Medium Security Prison in Cranston, Rhode Island, about which I started making this film.

As I started going to the visiting hours, and meeting the children who were visiting their parents, I realized that if I were to share any story about children experiencing parental incarceration, the stories should come from them directly. So often we tell stories about children through a top down perspective, informed by what we (adults) “know” about their psychology and how their lives will unfold. There was a desperate need for a film that allowed the children to speak for themselves, and fully represented their experiences in the rippling effects of our vast incarceration system.

You named the film after the boys and you name them as filmmakers, along with yourself, at the beginning of the film. How did they participate in telling their story beyond allowing you to film them?

The boys were and continue to be involved in the process in different ways depending on their interests. A large part of the trust I built with them was by sharing the equipment and letting them direct their own stories in what they wanted us to be a part of and to see. More so, however, this title-sharing was a decision that attempts to dismantle the traditional pedigree of filmmaker-subject relationships.

I feel that filmmaking is in large part a process of navigating the inherent powers we have over our subjects — power of privilege (race/class), resources, creative agency and ownership. Since it has been my practice to have this story be told directly from the child’s perspective, I felt that it was important to respect that agency in the film itself. I didn’t want, nor was it my place, to tell their stories. I recognized the importance of their voices in the conversation around criminal justice, that they were being silenced or unheard, and knew that I had resources to share to help elevate their voices within this issue-space. I couldn’t have done this work without them — none of us could make our films without our subjects — so therefore they are listed alongside me as filmmakers, and they legally own 10% of the film.

What is your relationship now with the families represented in the film and/or programs/advocacy for children with incarcerated parents?

I remain very close with all three boys and their families. They all have different support systems, so my relationship is different with each of them — but especially since Tre is now in foster care, I talk to him on the phone every day (if not a few times a day) and see him a few times a month. They are all very involved in the life of the film through the festival circuit and will be into distribution. We want this film to be a tool for them, to support each other and to advocate for themselves and other children with parents in prison.

We are developing a large impact strategy that spans several goals around both building communities of support for Children of Incarcerated Parents, and advocating for better access between children and their parents when they are in prison or jail. We are building out this strategy now and will be activating around it towards the end of the summer leading up to October, which is See Us Support Us month — recognizing Children of Incarcerated Parents. We have several organizational partners in these initiatives already, mostly in New York and Rhode Island, and are using the festival circuit to build out a wider network across the country.

It can be difficult to gain people’s trust, especially children in vulnerable or difficult situations; how did you develop trust and a rapport with your characters — especially the children?

Relationships. This was not a process of popping in and out of these kids’ lives to tell a story about how their parents’ incarceration is affecting them. I was there almost every week for 3 years, most of the time with a camera, but not always. We collected over 300 hours of footage, through which I never pressured intimate moments or scenarios based on the story I thought we were telling. I just spent time with them, listening and playing and documenting and collecting the stories from their lives as they were in front of us. I would safely venture to guess that about 60-70% of that footage is us just hanging out — playing with Legos, eating McDonald’s, going to the beach, birthday parties, Thanksgivings, Christmases, school days. Most of the time I would end a shoot day with, “Well, none of that is going to make it in the movie…”

The intimate scenes you see in the film are just blips in the time we spent with them documenting their lives, so when they would happen we were already there and already filming and the kids trusted us with these moments enough to capture them as they unfolded — and I would know that we had captured something special. They have described it to me as the camera just not being there after a while. It got to a point where Tre would ask us to come film with him, or to spend time together. Towards the end of production, Maison asked us, “When this movie’s finished, can you keep filming me?” They became a part of my life, and I became a part of theirs, and I came with my camera, and that’s how we were able to tell these stories together.

As a first-time feature director, do you have one piece of advice for aspiring filmmakers?

For new (and old) filmmakers, I have a few pieces of advice. First, find a good team. I could not have made the film I did without my producers and advisors — especially from the Chicken and Egg Accelerator Lab. It is so important to have feedback on your work, feedback on yourself, and people you trust to talk through the most challenging moments.

Second, know who you are. To take on the incredible responsibility of sharing stories that are not yours, you must understand your relative power in relation to your subjects. If your story is about marginalized people, it is even more important to understand your place in the histories and systems that interact in the stories you are sharing. Don’t try to tell other people’s stories. Allow your subjects to tell their own stories, and use the resources you have as a filmmaker to elevate and empower them. As filmmakers, no matter who we are and what our relationship is to our subjects, we must always be conscious of the power that film gives us. We must always navigate that power critically.

Third, be patient and allow your work to be a process. If you end up with exactly the film you set out to make, you probably haven’t made the best film about the subject you are exploring. Be resilient. Be adaptable. Ask lots of questions. Get comfortable being uncomfortable. Listen.

And my last piece of advice is to read. Lots of people think that if you want to be a filmmaker, you should be watching a lot of movies. I think it is more important to read a lot of books. There is so much to learn from 5000 years of humans writing things down!

What do you hope MFF audiences will take away from your film?

I chose to create this film in the open and collaborative mode of true cinema vérité, so that the viewer could get to know Tre, Maison and Dasan as I have — not defined by their parents’ incarceration, but existing in their own way, on their own terms, through the experience. There is no clear story arc — instead the audience is led through the ups and downs of life itself, an experience that is both riveting and personal. The film itself does not end in a call to action, or provide any single-sided answers to issues it presents. Therefore, the film does not center these children’s complex experiences around any specific issues or silo the issues that affect them, but instead allows audiences to shape their response around what they themselves can do for children in their lives professionally or personally.

Audiences are not leaving the theater armed with statistics, but rather with a personal and intimate connection to Tre, Maison and Dasan, which can be used to powerfully and radically shift they way people see and interact with the children in their lives. I encourage folks to visit our website for more specific resources and actions they can take.

What are you most looking forward to at MFF18?

I’m hoping to finally see some of the other films that have been around us at other festivals!

For more information on TRE MAISON DASAN, visit the film’s website.

Director Denali Tiller, Producer Rebecca Stern, and Dasan will attend both screenings of TRE MAISON DASAN on: Saturday, May 5, 2:15pm and Sunday, May 6, 4:15pm at the Clairidge Cinemas.

Interview by MFF Blogger Kimberly Cecchini

-

Genre