Danny Says

What do the Doors, the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, Alice Cooper, and the Ramones have in common? One man: Danny Fields. Fields isn’t a musician, but a press agent, record company executive, and editor who had an eye (and an ear) for groundbreaking bands and the skill to help usher many of them to fame. Motivated by a passion for the art, rather than the money, Fields had an almost unerring sense of which musicians could make a cultural impact. But, for all the discoveries he made and the groups he put on the map, Fields himself remains a virtual unknown. Danny Says aims to remedy that situation, with the help of the man himself, who amusingly provides a running narration over clips, photos, and montages. Though such legends as Iggy Pop, Judy Collins, and John Cameron Mitchell appear in interviews, along with others from the music industry, Fields is the star of the show—and has he stories to tell. Mostly unsentimental, almost always bitchily funny, Fields enjoyed working with “some of the most rebellious people.”

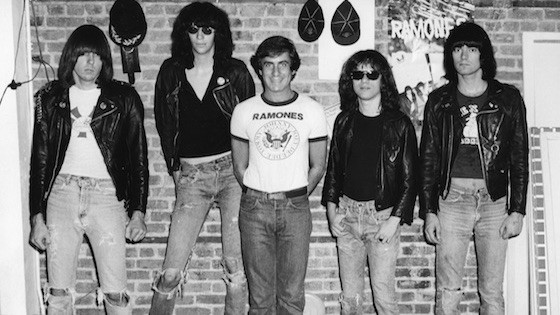

Born Daniel Henry Feinberg in 1939, Danny graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and then later attended Harvard Law. Gay in the days before the Stonewall rebellion, when being out wasn’t an option, he settled in Greenwich Village and began making musical and artistic connections. Admitting that “he was motivated by being in the right crowd,” Fields became a part of Andy Warhol’s Factory group, where he met Nico, a “showstopper” who eventually sang with the Velvet Underground, as well as Edie Sedgwick and Paul Morrissey, among others. Working as a journalist, Fields insinuated himself in the music scene, and broke the story about John Lennon saying the Beatles were bigger than Christ. He introduced Iggy Pop to David Bowie, and he dishes hilariously on Lou Reed, Jim Morrison (whose eternal enmity he earned—possibly even into the afterlife), Patti Smith, and such bands as the MC5, David Peel and the Lower East Side (creators of “The Marijuana Song”). Then came the Ramones, the band that seems to mean the most to Fields and that he managed for years. For Fields, the Ramones changed everything by throwing aside technique and proving to the world you didn’t necessarily need to be a good musician to play great rock ‘n’ roll. And their popularity opened things up for the whole punk scene, ultimately influencing such seminal groups as Clash and Nirvana. Indeed, clips of the Ramones in their early days at CBGBs have an irresistible sense of fun and power, and show exactly why Fields thought they “made everyone else seem old fashioned.”

Danny Says comes out in a poignant moment in Fields’s life, following a year filled with huge losses, including the deaths of Lou Reed and Tommy Ramone. “What matters is the smart people, the beautiful people,” he affirms.

For director Brendan Toller—who attended the screening with two of his animators, Emily Hubley and Matt Newman—the origins of this documentary lay in his first film, I Need That Record! The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store. He’d interviewed Fields for that work, but the footage ended up on the cutting-room floor. The two became friends and Toller decided to document Field’s life, a process that wasn’t easy: “It took 5 ½ years to get here,” he said. Toller had to go through piles of archival footage—“It was blessing and a burden to have that material,” he said wryly—and he interviewed 60 people. But he knew that Fields hadn’t written a book and that this was the first time he was telling his story—and important one in the history of music.

The audience had many questions about the production. The first speaker wondered how much the music rights had cost. “We’re still working on that,” Toller laughed. Another asked about distribution plans. Toller mentioned that the film had opened at the South by Southwest festival to great reviews, and they’re in the process of working out a distribution deal; he hoped it would happen by the end of the year. (Updates will appear on the documentary’s website, dannysaysfilm.com).

Toller asserted that the reason he could make the film at all is because Danny was willing to hang out with him and talk. Noting that Fields is now 75 years old, he once again insisted on the importance of getting the story out there. And in order to finance this labor of love, Toller worked three part time jobs until funding came . . . which happened much later. The whole project began with just him and his camera. As for getting Danny to agree to participate, it wasn’t easy. Fields’s initial reaction was that Toller should wait until after he died; then he decided the film could be made, but that he wouldn’t watch it. Finally, unexpectedly, he did see it, and though it was great. In a final fun twist, after the first good reviews, Fields decided Toller should produce a trilogy!

An audience member asked when Fields had retired from the business. Fields’s last artist was Paleface (who he signed in 1990), but the musician was alcoholic and hard to work with. Plus, Napster began to change things, the industry went through a transformation, and Fields didn’t really find people who interested him, who he felt he could push to the mainstream. Yet, Fields remains on the scene, still looking. When someone asked Toller how he decided where to end the film, he jokingly said that he quit when he reached an hour and 40 minutes! But more seriously, he felt that the Ramones were a good closing point, although Fields (ahead of the game, as usual) had become interested in country music just before singers like Garth Brooks exploded the genre.

Because Toller had earlier mentioned outtakes, someone asked whether he would post them online. Some, in fact, are already up—and more will come.

Written by MFF Blogger Karen Backstein