News

The Creative Journey in MADE A MOVIE, LIVED TO TELL

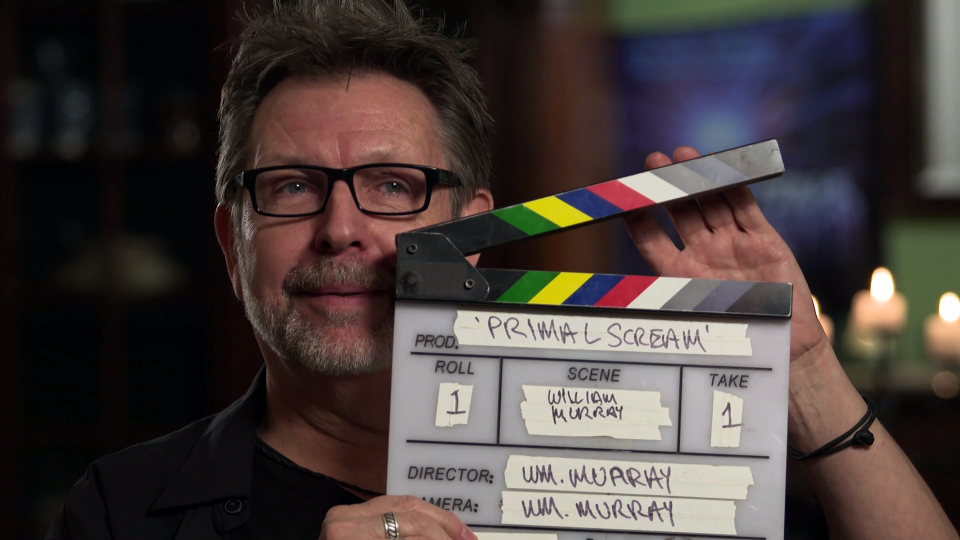

MADE A MOVIE, LIVED TO TELL revolves around the making of PRIMAL SCREAM, an obscure, shot-in-New Jersey 35mm feature, originally known as HELLFIRE. Filming began in 1983. The crew was young, inexperienced, and hopeful. The conceit – a futuristic film noir about a tough, dissolute private eye’s mission to wrestle from the hands of evil an explosive energy source mined in outer space – was highly ambitious. And there was no money, of course.

The stop-and-start production took over two years, and was punished with an endless series of troubles; some wrenchingly serious, some seriously comic. It took a toll on the cast and crew – there were fights and recriminations – but it also resulted in lifelong bonds among those involved. The documentary is as much about the emotional residue of PRIMAL SCREAM’s making as it is about its actual production: people wrestling with the lingering, bittersweet afterlife of a long completed, yet highly imperfect, creative journey.

Montclair Film Festival spoke with co-director Keith Reamer about the ups and downs of the creative process — then and now.

How would you describe MADE A MOVIE, LIVED TO TELL in your own words?

Bill Murray, DP Dan Karlok and I started shooting MADE A MOVIE, LIVED TO TELL with the idea of reconstructing the production of HELLFIRE — aka PRIMAL SCREAM — a long forgotten, made in NJ feature we (along with the rest of the cast of the documentary) mounted in 1983. At the time, we were young, aspiring, inexperienced filmmakers. The whole enterprise was quixotic, the production a baptism by fire and, at times, a comic calamity. Full of incident!

That is a big part of the story we tell in MAM,LTT and I think it is a lot of fun — but along the way of its making, we were able to delve deeper — as we knew we must — to explore the why, the how and the why not that lurks behind the taking of this kind of outsized, creative journey. To reveal the lasting effects of that journey — the undimmed bonds of memory and emotion between the makers of that nearly lost little film, and their coming to terms with the lingering residue of a highly imperfect, creative endeavor.

Memories, particularly older ones, can become hazy; people sometimes remember the same events in wholly different ways. Did you find that people had conflicting memories of the process of shooting the film?

Yes, indeed. But we tried to orchestrate the interviews to play towards the strongest recollections of our subjects. Whenever there were multiple accounts of an incident (such as ‘the arrest’ sequence) we tried to have the individuals’ stories structured in a way that they expanded, built and commented upon one another — even if there was a little disagreement of facts between them. In the end, I think some of the most effective stories are the ones fashioned out of the shared memory of multiple narrators. Of course, we also have several recollections built upon the memory of just one person — and they have their own rewards and pleasures.

Was there reluctance from any of the primary people involved in retelling the story of PRIMAL SCREAM? If so, why?

Surprisingly, not much. Well, perhaps a little from actors Sharon Mason and Ken McGregor — as it had been years since we all had been together, seen each other. Really since picture wrap! But it was certainly overcome. Making the initial contact, scheduling the shoots, traveling to them, reuniting — it really felt like an emotional unearthing, at times. In a good way as, once we were in the room together talking, time and distance and any lingering concerns seemed to fall away. For all of us. At least, I hope so. That kind of reinforced for Bill and me a feeling that we were doing the right thing in pursuing the story. That the experience mattered, the ties were real, and it was worth exploring in a film.

What would you say is the best piece of advice you could offer aspiring filmmakers?

First, find a story you love. Let your imagination run it down, explore it, develop it, and know it. But make sure you need to tell it. Making a film is a huge leap of faith, but if you believe in your story, you will believe in yourself. And then it will be incumbent upon you to do what you need to do to make your film.

What do you hope MFF audiences will take away from your film and about the filmmaking process?

Filmmaking is incredibly difficult, and it can take a toll. And not every film is great, or good. But even in the most flawed efforts, the most obscure, the most disadvantaged, there can be a form of grace that grows through the shared act of creating them. And of course…. surviving them!

As NJ natives, and with the film having been shot here, what does it mean to you to be screening your film in New Jersey?

It means everything. Back when we made HELLFIRE/PRIMAL SCREAM, we strongly identified as being, I don’t know… filmic outliers. Nobody was making films in our state. At the time, New Jersey was not the cool place it is today. It filled us with a sort of pride to be taking our chance in our own backyard. Making a run at success in a land where films. were. not. made. What did we know? Then to tell this story, all these decades later, and still being largely New Jersey-based filmmakers, premiering it in our own back yard… my (and DP Dan Karlok’s) hometown, it is a joy and the dream we have had for this film — and it is coming true.

Directors William J. Murray and Keith Reamer, DP Dan Karlok, and cast members David Swift, Kenneth McGregor, and Sharon Mason will attend an extended Q&A session after these screenings of MADE A MOVIE, LIVED TO TELL: April 28, 9:30pm and April 29, 12:30pm at the Clairidge Cinemas.

Interview by MFF blogger Kevin Walter